Cabaret, both as a musical and a movie, is celebrated for its striking depiction of pre-World War II Berlin through the focal point of the Kit Kat Klub. However, numerous fans and newcomers ponder: is the arranged melody darker than its cinematic counterpart? Let’s dive into this address by analysing the subtleties of each version.

The Origins and Core Themes of Cabaret

The origins of Cabaret follow back to John Van Druten’s play I Am a Camera, adjusted from Christopher Isherwood’s semi-autobiographical novel Farewell to Berlin. Both adjustments take after the story of English writer Cliff Bradshaw (or Brian Roberts in the movie) and his relationship with the captivating cabaret artist Quip Bowles amid the rise of Nazi Germany. The musical adjustment by John Kander (music) and Fred Recede (lyrics) extends upon these subjects with more stark and unsettling minutes .

The Musical: A Darker Interpretation

The organised form of Cabaret is broadly respected as darker than the film adjustment. This is basically due to its more unequivocal investigation of the political and social rot of 1930s Berlin. The musical’s tunes, especially those sung by the Emcee, such as “I Don’t Care Much” and “Tomorrow Has a Place to Me,” emphasise the inauspicious rise of totalitarianism. These scenes regularly feel more pointed and angry, driving the gathering of people to go up against the unsettling truths of the time head-on.

The finishing of the musical, which sometimes includes the Emcee uncovering a concentration camp uniform, can be particularly nerve racking. This stark update of the Holocaust is missing from the film, making the live production’s effect more prompt and chilling .

The Movie’s Approach to Darkness

Directed by Weave Fosse, the 1972 film adaptation featuring Liza Minnelli and Joel Dim keeps up a dim tone but presents it with cinematic pizazz and musical magnificence. The film emphasises Quip Bowles’ individual story more than the encompassing socio-political setting. Whereas it doesn’t totally avoid genuine topics, such as the effect of Nazism and anti-Semitism, it does less express the looming frightfulness of war compared to the arranged version.

The film incorporates important exhibitions like “Money, Money” and the piercing “Maybe This Time,” which, while effective, centre more on personal struggles and connections or maybe than the broader socio-political turmoil that the melodic digs into.

Key Contrasts in Narrating and Tone

Sally Bowles’ Characterization: In the film, Banter is depicted with a blend of allure and helplessness by Minnelli, making her to some degree more relatable and romanticised. To organize, Sally’s rash nature and the results of her choices are more articulated, displaying her as an awful figure cleared up in a disintegrating world.

Political Commentary: The musical regularly scatters numbers that act as allegorical reflections of societal breakdown, emphasising the dull parody inserted in tunes like “If You Could See Her.” The movie’s accentuation on character-driven dramatisation to some degree tempers this plainly basic approach.

Gathering of people Involvement and Impact

The organised musical’s intuitive and immersive nature contributes to its darker effect. Theatre preparations regularly include coordinated engagement with the gathering of people, which can open up the distress of observing the story unfurl. The film, whereas outwardly shocking and impactful, remains limited inside the boundaries of the screen, making a distinctive, maybe less visceral, experience.

Dull Subjects and Imagery in the Musical

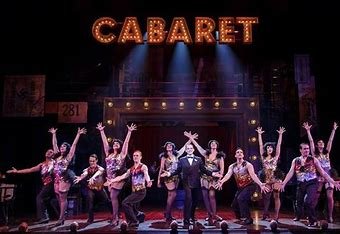

The organised generation of Cabaret places noteworthy accentuation on imagery and dull subjects, regularly passed on through its stark set plan and impactful choreography. The Unit Kat Klub, with its frequenting exhibitions driven by the Emcee, gets to be a microcosm of the rotting society around it.

The melodies and moves are bound with incongruity and inconvenience, reflecting the bent typicality that characterised the period’s ethical and political scene. This is especially apparent in numbers like “Willkommen” and “The Cash Melody,” which are bound with twofold implications around ravenousness, control, and approaching oppression.

In Summary:

Ultimately, Cabaret as an arranged musical jumps more profound into the grimness of its setting, advertising watchers and determined to see the individual and collective plummet into chaos. The motion picture adjustment, whereas keeping up the topical centre, presents these thoughts through a more cleaned and stylized focal point, coming about in a somewhat lighter, in spite of the fact that still impactful, involvement. For those drawn to stark authenticity and enthusiastic encounter, the arranged form of Cabaret holds the darker and more resounding power.

FAQs:

What are the primary contrasts in tone between the musical and the film of Cabaret?

A: The arranged musical of Cabaret is frequently considered darker than the film due to its more unequivocal investigation of topics like political rot and societal collapse in 1930s Berlin. The melodic incorporates frequenting exhibitions and stark symbolism that specifically stand up to the group of onlookers with the terrible substances of the time. In fact, the film, while holding a few of these topics, regularly emphasises character-driven stories and stylized cinematography, which can relax the effect of the darker elements.

What topics are more articulated in the melodic compared to the film?

A: The musical emphasises topics of wantonness, ethical equivocalness, and the rise of totalitarianism more expressly than the film. Songs in the musical as often as possible serve as political commentary, constraining the group of onlookers to stand up to the societal issues of the time. In the film, these subjects are displayed but regularly take a rearward sitting arrangement to individual stories and character development.

How does the gathering of people’s involvement vary between observing the melodic and the film?

A: Watching the musical is regularly a more immersive involvement, as live theatre permits for a coordinated engagement with the entertainers and the unfurling show. The crude vitality of live execution can increase the darker topics. In differentiate, the film offers a cleaned, visual involvement that can make the story feel more far off, possibly softening the passionate weight of the darker themes

How does the character of the Emcee differ between the two versions?

A: In the musical, the Emcee embodies a more menacing and chaotic presence, using irony and dark humour to highlight the unfolding societal crisis. This portrayal often creates a sense of discomfort that underscores the narrative’s seriousness. The film’s Emcee, portrayed by Joel Grey, offers a more charming and enigmatic performance, which, while impactful, lacks the same level of overt darkness found on stage

To read more, click here